Know Your Facts

Research behind "Being Atticus Finch"

The United States has one the largest prison populations in the world. According to a 2009 Pew Center report, roughly seven million out of a more than three hundred million Americans are under the control of the criminal justice system, either in prison, on parole or on probation. Out of those seven million, anywhere from 80-90 percent of those prisoners are indigent, meaning they are too poor to afford an attorney (Mann 2).

Based on these statistics, roughly 5.6 million Americans rely on public defenders – attorneys paid by the state to stand up for indigent defendants – to not only guide them through the justice system, but also to advocate for them and ensure their civil liberties are not unfairly taken. Public defenders play a key role in the U.S. justice system; unfortunately, many public defenders are defined by negative public opinion because they are being paid with “taxpayer dollars” to represent defendants from lower economic circumstances. These advocates also face difficult working conditions. They are sometimes unable to represent their clients to the best of their abilities because of a high number of caseloads - sometimes more than 200 cases per attorney at any given time. Public defender offices often also lack necessary resources and funding. The criminal justice system envisioned by the Founding Fathers was intended to be an adversarial system, one that puts one side, the prosecutor, against another, the defense, in order to assure liberties of the accused are not unfairly taken away.

Written in 1787, the United States Constitution is the supreme law of the land. All bills drafted by legislatures throughout the country at all levels of government, cannot go against any right given to Americans in the Constitution. The Sixth Amendment, which covers the “Rights of Accused in Criminal Prosecutions,” states, “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right…to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence” (US Const. amend. XI). While the Constitution states that an accused person has the right to an attorney, the interpretation of the Sixth Amendment was left up to the courts. Over the course of time, the processes’ interpretation has begun to define who, and under what circumstances, merits “the right to counsel.”

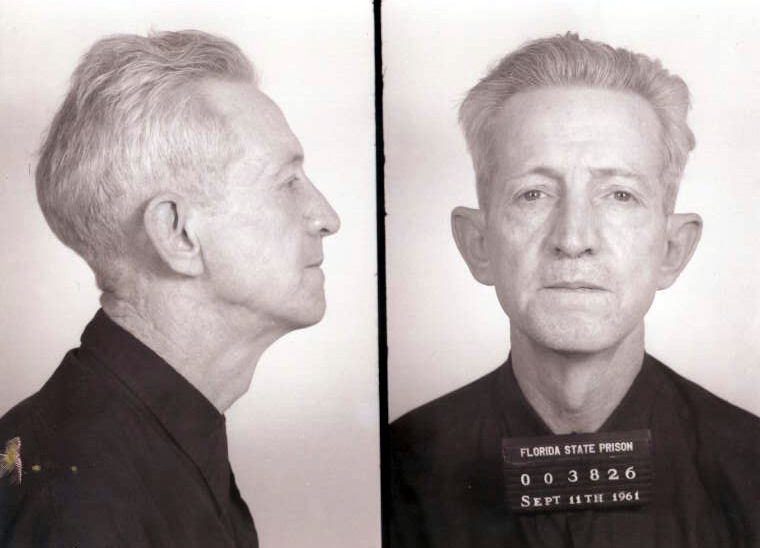

Public defenders have not always been available to indigent defendants. It was not until 1963, in the Supreme Court decision Gideon v. Wainwright, which was based on a Florida case, that the Supreme Court interpreted the Sixth Amendment to mean that everyone, rich or poor, has to right to counsel, and if the accused could not afford an attorney, one would be provided for him or her. The Court’s opinion stated, “…in our adversary system of criminal justice, any person hauled into court, who is too poor to hire a lawyer, cannot be assured a fair trial unless counsel is provided…The right of the one charged with crime to counsel may not be deemed fundamental to fair trials in some countries, but it is in ours” (Lewis 198).

Although a handful of cases had been brought before the Supreme Court about the accused's right to counsel prior to Gideon, the landmark case is viewed as the watershed decision because it interpreted the Sixth Amendment to cover all those charged with federal crimes, and under the Fourteenth Amendment, those charged with state and local crimes, as opposed to only death penalty crimes or other extreme felony cases. Gideon determined that all accused, no matter the crime, had a fundamental right to an attorney. But Gideon v. Wainwright was not the end of the fight for the right to counsel under the Sixth Amendment. In the 51 years since the Court's Gideon decision, the right to counsel has been expanded to include juveniles, misdemeanor offenses and, as recently as 2008, the right to counsel at the accused’s initial court appearance.

Although Gideon expanded the interpretation of the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments, the Supreme Court did not rule on who would represent the indigent defendants, and how the work of those attorneys would be funded. Because of this, public defender systems across the country, created in the wake of the Gideon decision, are strapped with excessive caseloads due to the paltry funding their offices receive. The lack of funds and resources is not the only issue public defenders combat every day. Because of an unfortunate public stigma, public defenders find themselves having to justify their profession almost daily, even to the very clients they save. “There is absolutely a stigma. If you don’t know…what the work is actually like and how much hard work your average public defender puts into the job, it’s easy to believe the cultural stereotype that goes with it,” says Katherine O’Connor, an Assistant Public Defender for Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Public defenders have been called “public pretenders” by their clients, and have been asked, “so you’re just doing this until you become a real lawyer?” Public defenders are often asked by people in the community, “how do you sleep at night?” or as Kevin Davis writes in his book Defending the Damned about the Murder Task Force in the Chicago Public Defenders Office, “how can you defend those people...implying that public defending is less than noble, that these lawyers must explain themselves…it suggests that public defenders represent already guilty clients unworthy of a vigorous defense…”(Davis x).

Many public defenders face these questions regularly, the majority of Americans support providing legal services for those who cannot afford them, according to a 2002 National Study of Public Opinion on Indigent Defense. Paradoxically, 54 percent of Americans believe the clients of public defenders are guilty (Belden 2). Overall, Americans understand the importance of having public defenders based on the rights given to all Americans in the Constitution; however, they may not understand fully the work that public defenders do.

When a person is arrested, they are asked if they can afford an attorney or if they would like one to be appointed to them. If they choose they latter, they defendant fills out a form listing his or her assets. Based on that, the judge then decides whether or not the defendant qualifies for a court appointed lawyer. If the defendant qualifies, their case file is given to the public defenders office at which time it is passed on to the next available attorney in no particular order. When a public defender receives a new case, they begin looking through the file, sometimes meet with their client before the first court date, but more often then not, the first time a public defender meets their client is in court on the day of the client’s hearing. Because of this, public defenders can’t devote as much time as they may want to on every given case. Once the country has an understanding of the importance of public defenders, other than simply representing “criminals,” P.D. offices can begin not only to gain more respect, but more funding and resources as well.

Not every state has state-funded public defender offices. There are three model systems for assigned counsel: public defender programs made up of salaried attorneys who only represent indigent clients; assigned counsel systems, which are overseen by judges who appoint clients to lawyers; and the contract system, in which private or non-profit companies have a contract with the courts and represent indigent clients for a set amount of money (Wice 10-15). There is no right or wrong way to handle indigent counsel, according to the Constitution. It has been left up to the states and each state, including the District of Columbia, employs a different system. Because of this, some offices are more successful than others in keeping caseloads manageable and ensuring competent defense for every client.

In 2007, the Bureau of Justice Statistics did a census of public defender offices. The census found that public defender offices were funded at the county or state level, with 22 being funded by the state, while 27 and Washington, D.C., were funded on the county level (Langton 2). The Bureau’s other finding included the fact that the 957 public defender offices throughout the country handled more than 5.5 million cases in 2007 with their costs exceeding $2.3 billion (Langton 1). The more successful offices are the ones with larger budgets who can hire more attorneys and support staff. Offices funded at the state level tend to have less funding and therefore their attorneys have more obstacles to face. For example, the census shows the total expenses for state-funded offices was just over $800,000, whereas county-funded offices had funding of more than $1 million (Langton 5).

When public defender offices are short on funds, they cannot hire the amount of attorneys necessary to handle the caseloads and the support staff, such as investigators, to assist the public defenders in an expedient manner. “Funding for indigent defense services is shamefully inadequate. The lack of funding impacts virtually every aspect of indigent defense systems” (American Bar Association 7). Without adequate funds, and the additional staff afforded to offices with higher funding, clients may not always receive the care and attention to their case as a retained attorney, one hired from a private firm.

When public defenders are overburdened with cases, they are unable to give every case and client the care and attention each deserves. Sometimes the situation can be so drastic, attorneys admit to not providing every case with the competency they are ethically required to provide. “Defense lawyers are constantly forced to violate their oaths as attorneys because their caseloads make it impossible for them to practice law as they are required to do according to the profession’s rules, ” (National Right To Counsel Corporation note 2 at 7). Public defenders work tirelessly to give all their clients more than adequate representation; however, these efforts sometimes fall short because, at the end of the day, they don’t always have the tools and financial resources needed to adjust their caseload which would increase the quality of representation they give.

The lack of funding for public defender offices is only part of the excessive caseloads problem. Other factors contribute to the amount of caseloads public defenders must handle at any given time. Prosecutors, for example, have the ultimate control of the number of arrested people who end up being charged (Rapping). For every person charged with a crime, it is one more case in a prosecutor’s caseload. Because of this, both prosecutors and public defenders have a relatively equal numbers of cases at a time; however, the prosecutors, it can be argued, can handle their cases more efficiently by trying to plea every case and avoid trial.

Many indigent defendants are unable to afford bond, forcing them to stay in jail as they wait for their cases to move through the justice system. While in jail, they aren’t working and therefore can’t provide for their family. If they are female, they typically are the sole caretakers of their children. The longer they sit in jail, the greater risk they are at for their children being taken away by child protective services. The sooner defendants can get out of jail, the less their family lives will be turned upside down. Prosecutors use this to their advantage by offering pleas with significantly shorter sentences if the defendants take the plea within a shortened time frame than what they face if they choose to go to trial (Rapping 517). Defendants, with sometime complete disregard to their possible guilt, feel pressure to accept these pleas so they spend less time in jail before having proper time to discuss their case with their public defenders. If the public defenders had fewer cases, they would have more time to spend with their clients to weigh all possible options before the clients felt a plea was the only solution to their legal troubles.

Another factor that contributes to the high number of indigent cases is laws, both federal and state, that unintentionally target poor minority communities. In Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, she discusses how the War on Drugs, which began in the 1980s during the Ronald Reagan Administration, has made these communities more susceptible to arrests than more affluent white communities because the poorer communities are an “easy target” for police. The War on Drugs is responsible for increasing the prison population in the United States about 1,100 percent between 1985 and 2000 (Alexander 59). Along with the War on Drugs, came the “tough on crime” platform many politicians, including President Bill Clinton, chose to run on in the 1990s. With a new "three strikes and you're out" attitude came laws that punished repeat offenders drastically more than first-time offenders. The law nicknamed after an inflexible baseball rule, endorsed by Clinton in 1994, produced “new federal capital crimes, mandated life sentences for some three-time offenders and authorized more than $16 billion for state prison grants and expansion of state and local police forces (Alexander 55).” This increased the number of arrests, which in turn, increase the number of cases for public defenders.

With the prison population on the rise, the amount of work for public defenders is on the rise as well, though funding is not. Now is the time to begin reforming public defender systems that aren’t as efficient as they could be and press legislatures to increase funding for indigent defense. Jonathan Rapping, a former public defender in Washington, D.C., created the organization Gideon’s Promise. This organization brings the funding issue public defenders face on a daily basis to the forefront of the discussion. Not only does Rapping’s organization aid in the training of public defenders, but it also assists offices struggling with resources and efficiency. As Rapping states in his journal article, “Who's Guarding the Henhouse? How the American Prosecutor Came to Devour Those He Is Sworn to Protect,” “ justice is determined by how faithful the system is to the process too important to our constitutional democracy.”

The current justice system has its faults in every aspect of the process. Public defense is simply of part of a larger system working toward the goals of our Founding Fathers. But when one part of the system fails, the entire system fails; failing those affected directly by it and failing the country as a whole. Because of this, it has never been more important to begin fixing the problems that we can fix, in order to maintain the country comprise of "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness" (Declaration of Independence) originally envisioned by the Founders in 1776.

Case Study: Mecklenburg County

With just over sixty assistant public defenders, seven investigators and two in-house social workers, the public defenders office in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina is one of the largest is the states. Lead by Public Defender Kevin P. Tully, the office boasts of practicing a holistic approach to public defense. Instead of treating each case, the office treats the whole person. For example, an attorney may have a client with a drug charge. The attorney will work with the client on the legal charges, but will have one of the social workers in the office assist the client in finding treatment if they have a drug problem, or housing if they are homeless. The idea behind a holistic law practice is that by assisting each client not just with their legal troubles, but also with the life situations that may have led to the legal issues, there is a greater chance in changing the client’s legal pattern and establishing a sense of stabilization, all which lead to a decrease in arrests.

According to Chief Public Defender, Kevin P. Tully, the Mecklenburg office represents 18,000-20,000 cases in a given year. With the 60 lawyers in the office, that is a little over 300 cases per lawyer per year. Mecklenburg County has the assistance of private attorneys in the county to aid with the caseloads, something that is not the case throughout the country. Personally, Tully said in an interview, “at one point in my career, I had 110 clients, they were all facing serious felony charges, seven were facing murder charges and four were facing the death penalty.” He knew he could not provide effective counsel to each of his clients and asked his boss at the time to help ease his caseload. Now, as the Chief Public Defender, Tully runs the office in a way to avoid being at “the back-end of the problem,” to avoid over-burdening his attorneys and guaranteeing effective counsel for the clients his office works for.

Bibliography

Alexander, Michelle. "Go to Trial: Crash the Justice System." Sunday Review. New York Times, 10 Mar. 2012. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/11/opinion/sunday/go-to-trial-crash-the-justice-system.html?_r=0>.

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: New Press, 2010.

American Bar Association Standing Committee On Legal Aid And Indigent Defendants. "Gideon's Broken Promise: America's Continuing Quest for Equal Justice." American Bar Association. American Bar Association, Dec. 2004. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_aid_indigent_defendants/ls_sclaid_def_bp_right_to_counsel_in_criminal_proceedings.authcheckdam.pdf>.

Belden Russonello & Stewart Research And Communications. "Americans Consider Indigent Defense: Analysis of a National Study of Public Opinion." Indigent Defense Criminal Justice Public Opinion. National Legal Aid And Defender Association, Jan. 2002. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.nlada.org/DMS/Documents/1075394127.32/Belden%20Russonello%20Polling%20short%20report.pdf>.

Boruchowitz, Robert C., Malia N. Brink, and Maureen Dimino. "Minor Crimes, Massive Waste: the Terrible Toll of America's Broken Misdemeanor Courts." NACDL Reports. National Association Of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Apr. 2009. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.nacdl.org/reports/misdemeanor/>.

Charles, Stephen D., Elizabeth Accetta, Jennifer J. Charles, and Samantha E. Shoemaker. "Indigent Defense Services in the United States, FY 2008-2012." Bureau Of Justice Statistics, July 2014. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/idsus0812.pdf>.

Cohen, Andrew. "How Eric Holder Can Help Public Defenders and Their Clients." National. The Atlantic, 23 Aug. 2013. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/08/how-eric-holder-can-help-public-defenders-and-their-clients/278976/>.

Davis, Kevin. Defending the Damned. New York: Atria Books, 2007.

Fickman, Robb. "Judges Must Act to End Jail Overflow." Outlook. Houston Chronicle, 9 Aug. 2009. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.chron.com/opinion/outlook/article/Judges-must-act-to-end-jail-overflow-1747232.php>.

Gideon v. Wainwright, 373 U.S. (1963)

History Of Right To Counsel. National Legal Aid And Defender Association, 2011. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.nlada.org/About/About_HistoryDefender>.

Holder, Jr, Eric H. "Defendants' Legal Rights Undermined by Budget Cuts." Opinions. The Washington Post, 22 Aug. 2013. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/eric-holder-defendants-legal-rights-undermined-by-budget-cuts/2013/08/22/efccbec8-06bc-11e3-9259-e2aafe5a5f84_story.html>.

“Indigent Defense Gets A New Look from Attorney General Eric Holder.” MPR. St. Paul. 10 Mar. 2010. Radio.

Langton, Lynn, and Donald J. Farde, Jr. "Census of Public Defender Offices, 2007." Bureau Of Justice Statistics Selected Findings. Bureau Of Justice Statistics, 2009. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/idsus0812.pdf>.

Lefstein, Norman. "Securing Reasonable Caseloads: Ethics and Law in Public Defense." American Bar Association. American Bar Association, 2011. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/books/ls_sclaid_def_securing_reasonable_caseloads.authcheckdam.pdf#page=7>.

Lewis, Anthony. Gideon's Trumpet. New York: Random House, 1964.

Mann, Phyllis E. "What Do We Mean When We Say "Indigent Defense"." What Do We Mean When We Say “Indigent Defense?”. National Legal Aid And Defender Association, 2010. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://nlada.net/sites/default/files/na_whatdowemeanwhenwesayindigentdefense.pdf>.

"National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals: the Defense." NAC Standards for the Defense. National Legal Aid And Defender Association, 1973. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://nlada.net/sites/default/files/nac_standardsforthedefense_1973.pdf>.

National Legal Aid And Defender Association. Five Problems Facing Public Defense On The 40th Anniversary Of Gideon V. Wainwright. National Legal Aid And Defender Association, 2011. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.nlada.org/Defender/Defender_Gideon/Defender_Gideon_5_Problems>.

National Right To Counsel Corporation. "Justice Denied America’s Continuing Neglect of Our Constitutional Right to Counsel." Constitution Project, Apr. 2009. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.constitutionproject.org/manage/file/139.pdf>.

Rapping, Jonathan A. "Who's Guarding the Henhouse? How the American Prosecutor Came to Devour Those He Is Sworn to Protect." Gideon's Promise. Gideon's Promise, 10 June 2010. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://gideonspromise.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Who-is-Guarding-the-Henhouse.pdf>.

The Spangenberg Group. "Statewide Indigent Defense:2006." American Bar Association, 2006. Web. July & Aug. 2014. <http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_aid_indigent_defendants/ls_sclaid_def_2006statewide_id_systems.authcheckdam.pdf>.

U.S. Constitution. Amend. XI

Wice, Paul B. Public Defenders and the American Justice System. Westport: Praeger Publishers, 2005.